2007

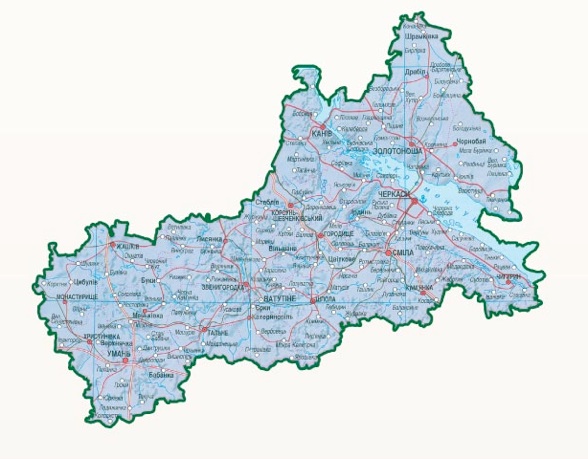

My father comes from the village of Antypivka, in Cherkasy oblast (state), but none of our relatives remain there. Some, like his family, were forcibly evicted from their house and had their land and all their goods appropriated by the Soviets during collectivization in the 1930s. Others married and moved to nearby villages. Yet others moved to bigger cities for the opportunity of a better life.

I try to visit them whenever I'm in Ukraine, and our get-togethers have become a big family event. Everyone who can tries to make it. My relatives from nearby Cherkasy come, and another branch of the family who were resettled in Rivne oblast also show up. We have a full house, with good Ukrainian food, lots to drink and, if Inna has her way, singing as well. Summers are best, as Aunt Tanya's daughter and her family come to visit there from Zaporizhia, and usually show up. Last year went particularly well, as Vera and Yarko were in town, and we had five boys running around.

But this year it was autumn when I visited, so there were fewer of us. Still, Serhiy from Cherkasy finally brought his wife to meet us, along with his stepdaughter and relatively newborn son. We ate and drank, reminisced, looked at the photos I'd brought, and had a lovely time.

Main UKRAINE Page

___________

-

1.During the period of forced collectivization, peasants were forced to give up their land to the collective, along with their horses, cows and pigs. They were allowed to stay in their houses, though. Unless, of course, they were a “kurkul” (Russian "kulak"), defined by Britannica as "a wealthy or prosperous peasant, generally characterized as one who owned a relatively large farm and several head of cattle and horses and who was financially capable of employing hired labour and leasing land."

My grandfather was a carpenter, and had a small business. He owned two hectares of land, and sometimes employed help. This condemned him in the eyes of the Soviet authorities. First the family was thrown off of their land; they lived with relatives, and then found a place in Zolotonosha. Later he was arrested, and taken away. They never saw or heard from him again. The family had suspected that, like many kurkuls, he had been sent to Siberia. Only recently I learned that he had probably been shot, along with many others, in Cherkasy.

Zolotonosha